The New York Times

Mar. 11, 2019

by Vanessa Barbara

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — “Five years ago, a Brazilian woman in labor was detained by police officers and forced to deliver by C-section.

The woman, Adelir de Goes, had already had two cesarean sections — an all-too-common procedure in my country — and was hoping to deliver her third child vaginally. But her baby was in breech presentation. Doctors felt that a vaginal birth would put the baby in danger.

And so they got a court order for a mandatory operation. Ms. de Goes was almost fully dilated and preparing to return to the hospital when nine police officers knocked on her door to take her away. In the hospital, she was anesthetized, and operated on without her consent. Women’s rights groups denounced the procedure as an assault on her autonomy and a violation of her right to make informed decisions about her baby’s health as well as her own.

But if Ms. de Goes’s case was especially notorious, it was also far from exceptional. According to a 2010 survey, one in every four Brazilian women has suffered mistreatment during labor. Many of them were denied pain relief or weren’t informed about a procedure that was being done to them. Twenty-three percent were verbally abused by a health professional; one of the most common insults was “Na hora de fazer não chorou” (“You didn’t cry like that when making the baby”).

Another survey found that, in 2011, 75 percent of women in labor in hospitals were not provided water and food (last year, I became one of them), although this practice is not supported by scientific evidence. The World Health Organization recommends that low-risk women in labor eat or drink as they wish.[

But some doctors are unaware of the concept of “wish” as it relates to women. Faced with a patient who refuses a procedure, they do it to her anyway. “I am the boss here,” they insist.

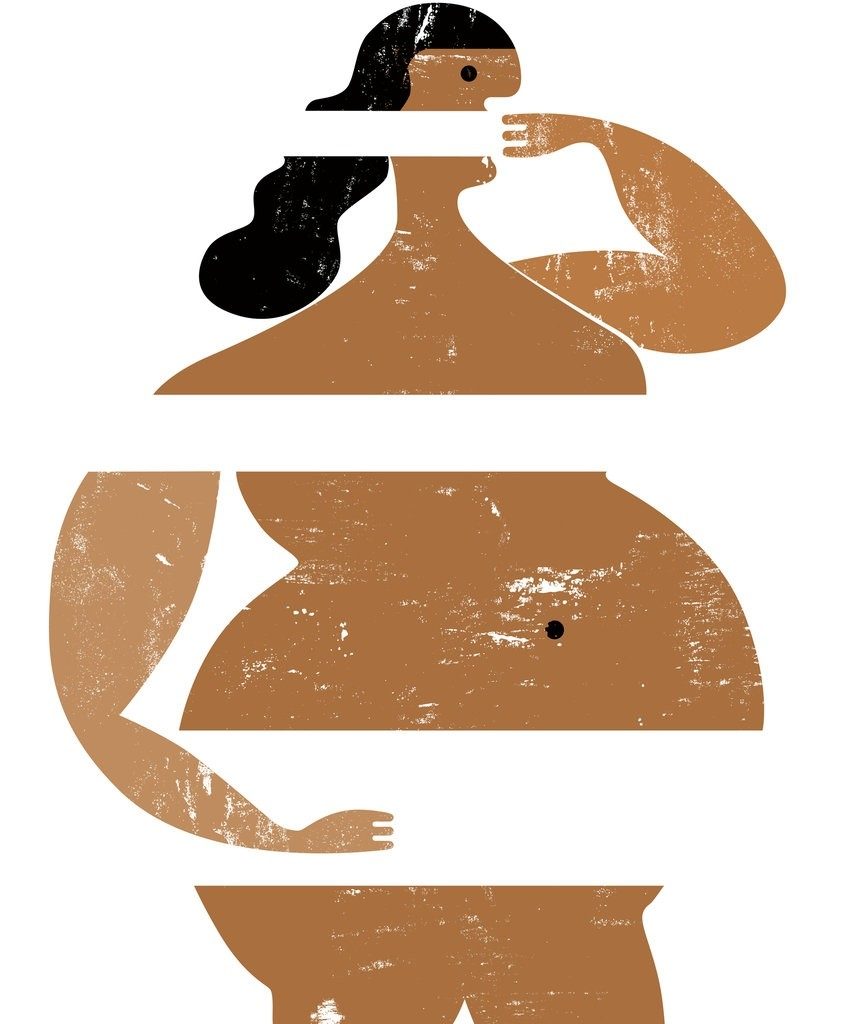

Outraged by this enduring abuse, Latin American women in the last few decades have helped to identify and to legally define a different type of gender-based violence: “obstetric violence.” It refers to disrespectful, abusive or neglectful treatment during pregnancy, childbirth, abortion and the postpartum period.

One example is episiotomy, a surgical cut in the vagina made during labor that has been proven ineffective and even harmful when performed routinely. Doctors still perform it in Brazil, with or without the women’s consent. And when it’s suturing time, they sometimes include an extra stitch to supposedly tighten the vagina to increase male pleasure — a “husband stitch.” (Five years ago, in Rio de Janeiro, an obstetrician was caught on video asking a patient’s husband, “Do you want it small, medium or large?”)

The struggle against obstetric violence in Latin America began in the 1990s with activists’ efforts to disseminate evidence-based practices in maternal and newborn care. Those efforts were encouraged by a document issued by the World Health Organization in 1996 (“Care in Normal Birth: A Practical Guide”), which warns against turning a normal physiological event into a medical procedure, via “the uncritical adoption of a range of unhelpful, untimely, inappropriate and/or unnecessary interventions, all too frequently poorly evaluated.”

Within a few years of the report, Uruguay (2001), Argentina (2004), Brazil (2005) and Puerto Rico (2006) approved laws granting women the right to be accompanied during labor and delivery. Brazil and Argentina also developed broader legislation encouraging the “humanization” of childbirth.

In 2007, Venezuela became the first nation to create a law specifically addressing obstetric violence. Two years later, Argentina enacted a similar law; it was followed by Panama, multiple states in Mexico, Bolivia (with a law referring to “violence against reproductive rights” and “violence in health services”) and El Salvador (this one calling for dignified treatment in maternal and reproductive health services).

These laws came not a moment too soon. In Latin America, reports of obstetric violence have been extensively documented. They’ve even come to be expected, as if this is the price women have to pay for having any sexuality. The most common kinds of mistreatment are non-consensual procedures (including sterilization), non-evidence-based interventions like routine episiotomies, and physical, verbal and sexual abuse.

We can only wonder why obstetric abuse is so ubiquitous in Latin America, a place where motherhood is often sanctified. Maybe it’s precisely because of this. In our conservative, patriarchal societies, a woman’s true vocation is to be a mother. We must sacrifice ourselves to fulfill our biological destinies. This means submitting to the wills of husbands and doctors; selflessness and devotion are our most prized attributes. And if we remain long-suffering saints, we cannot gain sexual consciousness, or bodily autonomy.

Putting a name to the practice of obstetric violence is the first step toward standing up against it, and so, of course, doctors have begun fighting back. Last year, Brazil’s Federal Council of Medicine condemned the term obstetric violence as an aggression toward doctors bordering on “hysteria.” Note that the council did not condemn the violence itself, merely the word choices of the victims. I wonder if it used the word “hysteria” on purpose.

In a similar vein, in February, Rio de Janeiro’s Regional Medical Council issued a resolution forbidding obstetricians from signing personal birth plans, calling them a deleterious “fad.” The council also argued that childbirth is risky and demands quick decisions that doctors should be able to make without the fear of legal repercussions. “There is no time to explain what will be done or to revoke birth plans,” it stated. According to the council, obstetric violence is “another invented term to defame doctors.”

It is disappointing to see that some doctors are more concerned with the way this semantic “aggression” injures their prestige than with the concrete, horrendous reality of abuse that abounds against women in childbirth, not only in Latin America but elsewhere. It’s plain that they resent the limitations on their authority.

But pregnancy is not an exception to the idea that a capable patient has the right to make informed decisions about her medical care. Health care providers should not “explain what will be done” to pregnant women; they should honestly discuss our choices and respect our bodily autonomy.

And choosing another term such as “disrespect during childbirth” instead of “obstetric violence” will not soften the atrocities often committed by caregivers in the name of “doctor knows best.”

Vanessa Barbara, a contributing opinion writer, is the editor of the literary website A Hortaliça and the author of two novels and two nonfiction books in Portuguese.

A version of this article appears in print on March 12, 2019, on Page A23 of the New York edition with the headline: An Epidemic of Obstetric Violence.