Credit: Zeloot

The New York Times

June 18, 2018

by Vanessa Barbara

Contributing Opinion Op-ed Writer

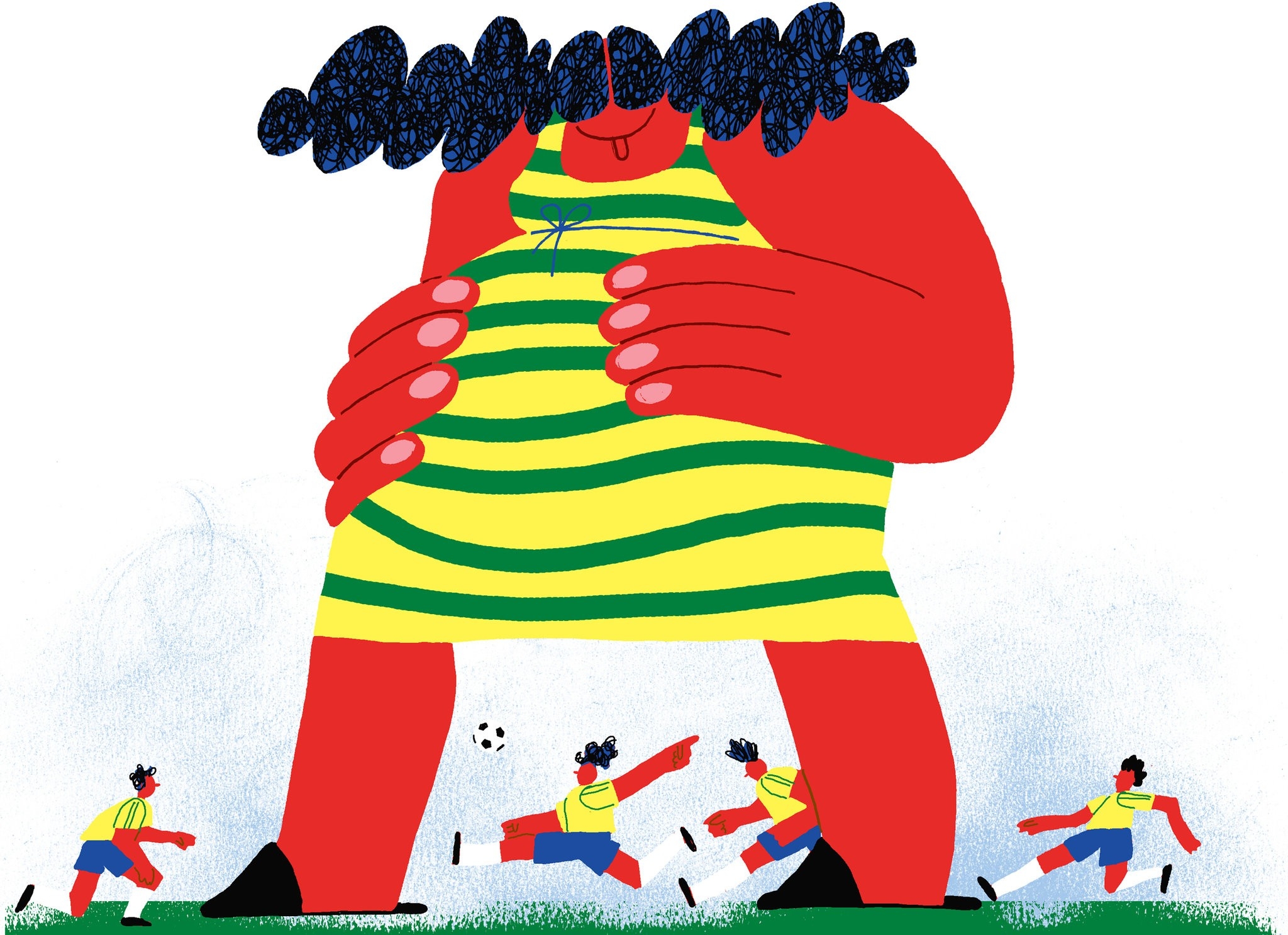

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — Brazil becomes an odd place during the World Cup.

People are given time off from work when the national team is playing, so that they can go home and blow horns for three hours straight. Media coverage becomes even more soccer-oriented than usual: Topics like why Brazil’s mascot (Canarinho Pistola, whose name roughly translates as “easily pissed-off canary”) is better than FIFA’s official 2018 one (Zabivaka, a soccer-playing wolf) are suddenly deemed newsworthy. Politics grinds almost to a halt, even though every World Cup year is also a major election year. For a month, everything happens against a backdrop of soccer-related euphoria.

That worries me, because my daughter is due to be born on June 22, the day Brazil plays Costa Rica. It’s true that the exact date cannot be predicted, but she’ll certainly arrive sometime during the tournament. And everybody knows it’s easier to give birth on your own (with the help of some YouTube instructional videos) than it is to get the attention of any Brazilian during the World Cup — this applies to taxi drivers, to the staff in the hospital and even to the baby herself.

I know this because I was born during Brazil’s game against the Soviet Union in the 1982 World Cup, in Spain. It was an arduous childbirth — and it didn’t help matters that it coincided with an arduous match, making it the worst timing ever.

That day, my mother started to feel mild contractions in the morning and went to the hospital around noon, driven by my father and grandfather. After filling out admissions paperwork, she casually suggested that the two of them should go home, because everything would probably take some time. She didn’t even have the chance to repeat these words before they were gone; the first match of the day, Italy versus Poland, had already begun, and it would be followed by Brazil versus the U.S.S.R. at 4 p.m. My grandmother was mortified when she saw the two men coming home alone, but she couldn’t persuade them to go back.

While Italy and Poland faced off in a tedious and ultimately scoreless match in the city of Vigo, my mom dressed in a hospital gown and laid back on a table, where apparently, a team of nurses helped break her water. (She’s not sure of this, since nobody said anything about the procedure, but as soon as she got up, there was a puddle on the floor.) They then took her to a small room surrounded by glass windows. She settled in, and the nurses left to go about their work, pausing periodically in a TV room nearby, where the Brazil versus U.S.S.R. match was about to begin.

Those first few hours didn’t go smoothly. It was my mother’s first time going through normal labor — my older brother was born via a speedy C-section right after she ate eight slices of pizza — and she wasn’t quite prepared for what to expect. As the pain got more intense, she tried to breath through it and imagined she was somewhere else.

At the Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán Stadium, in Seville, things weren’t going well either. Local fans, who’d started out rooting for Brazil, changed their minds at the 17-minute mark, when the referee failed to award a penalty to the Soviets after one of our players pulled down one of their forwards as he was about to shoot. Spanish fans booed loudly and started to shout “Fuera Brasil!” (Out Brazil!)

As the pain became overwhelming, “I started to flail my arms and legs awkwardly,” my mom told me later. Brazil’s national team seemed to follow similar tactics, running aimlessly around the field and misplacing even the easiest passes. They also collided countless times with the photographers gathered around the pitch. Everything was falling apart. That year, Brazil had put together one of our best teams in history, but come game day, the players were acting as if they’d been taken by surprise by a sudden increase of prostaglandins and a baffling cervical dilation.

At the 34-minute mark, the Soviets took one lazy shot at the goal, which our goalkeeper let slip through his hands with equal laziness. The score was now 1-0, them. In São Paulo, my mom — scared and alone and epidural-less — was in despair. Unfortunately, the women in my family are very restrained — I’m trying to correct this terrible flaw for the next generation — so she didn’t scream. She just feverishly hoped that someone would appear to take care of her.

But the second half had just begun in Seville, and finally things were starting to look auspicious: Brazil went on the attack and local fans resumed their cheering. “I really don’t know what time it was, but somebody in the TV room finally saw me floundering and came to help,” my mom said.

Nobody told her anything about how dilated she was (nor did they tell her the score), but they did put her on the gynecological table, where two nurses covered her knees with a blue cloth. The obstetrician told her to push, but by then she was too exhausted to even breathe. She got an episiotomy. One of the nurses put her hands on my mother’s belly and started to help her.

I like to think that I was born at the exact moment when Doctor Sócrates — one of our most beloved players, a midfielder who was also a political activist and had a bachelor’s degree in medicine — dribbled past two Soviets, stabilized the ball as if preparing a patient for a surgery and shot it into the corner of the net. By then, my head had already emerged — or so I imagine — but at 7.5 pounds and 18 inches, I had to really stretch to see into the TV room and watch the Doctor’s feat, and as a result, I made it the rest of the way into the world (and immediately became a fan of Corinthians, the team for which he played.) Nobody heard me cry, because they were too busy celebrating.

“It’s a little girl,” the nurses announced. Doctor Sócrates marked the occasion by holding his fists up high in a gesture of victory.

The nurses cleaned me off, wrapped me up and showed me to my mother as if I were the original Jules Rimet Trophy. My mother’s first impressions of me were that of a cute, if very hairy, little baby. But I was born with jaundice and had to be quickly taken to the nursery for phototherapy. As my mother delivered the placenta and nurses sutured the cut, she heard some other shouts that could have been reactions to Brazil’s second and winning goal. Or not. It’s impossible to know for sure the chronology of that afternoon’s events.

All we know is that my father and grandfather came back after the end of the match and they were both very pleased with the efforts of our national team.

Vanessa Barbara, a contributing opinion writer, is the editor of the literary website A Hortaliça and the author of two novels and two nonfiction books in Portuguese.