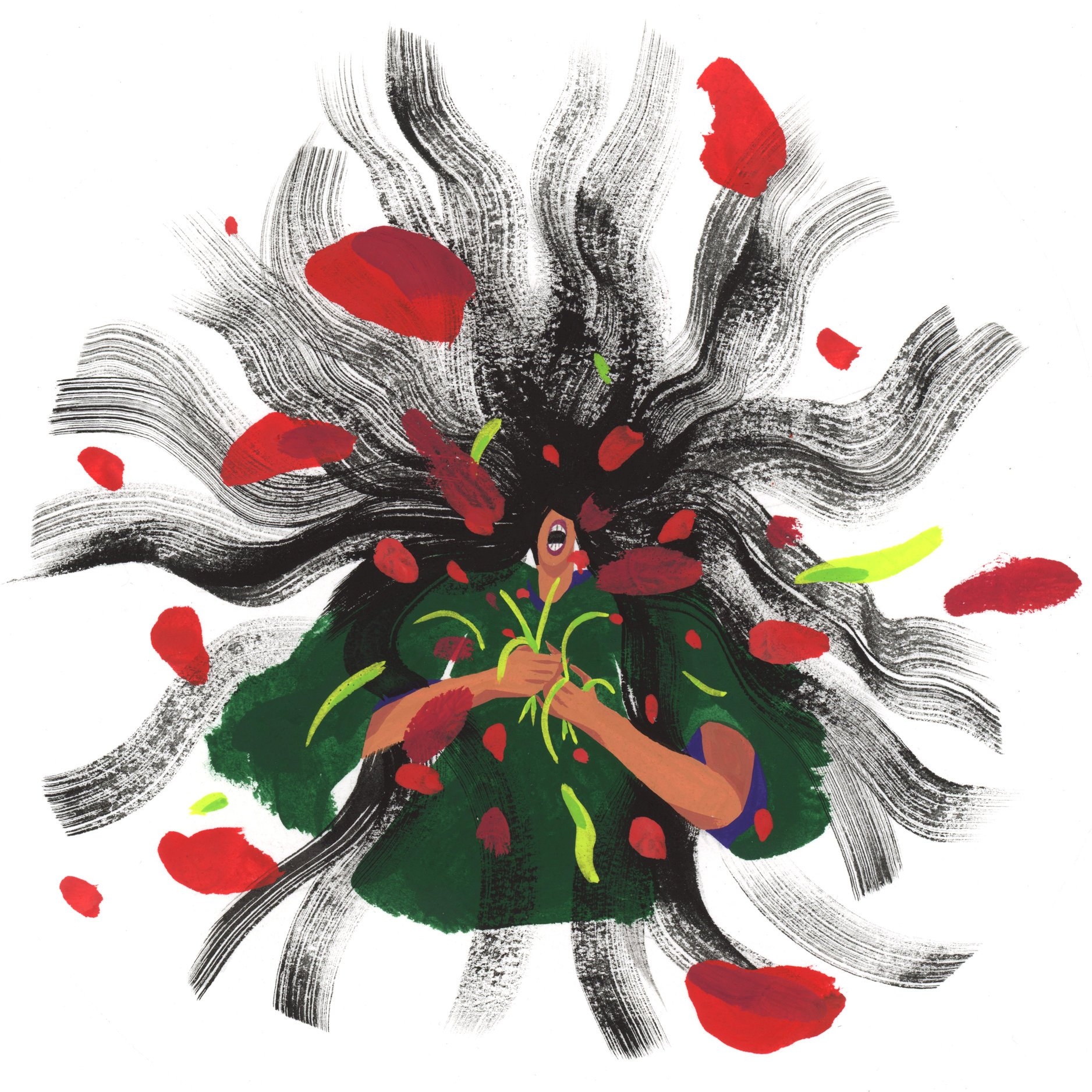

Credit: Ping Zhu

The New York Times (Sunday Review)

November 12, 2017

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — When I was 7, I joined the Brazilian Girl Guides. One of the basic laws of the guides was that a girl should be “courteous and delicate.” (These days they only emphasize the “courteous” part.) I remember being taught to abide by the following requirements to earn one of the guides’ coveted badges: A girl needs to know how to treat authorities, how to show deference to people, how to listen and speak at the right time and — my favorite — how to address people without yelling.

In September, I took my first classes in women’s self-defense. They definitely left some marks on me (besides the bruises). I could finally understand, in my body, the full extent of the violence and humiliation that we women in Brazil are meant to swallow during our lives, always with meekness and grace. Lowered head, slumped shoulders, stiff neck, dropped gaze: Our whole body is often shrunken and pointed inward, as if we are trying to be as small a target as possible.

For a long time, showing obedience and good manners were considered the most important things for a girl to learn. Even now, especially in developing countries like mine, this has barely changed: The worst thing a woman can do is speak up for herself and spread ideas that are not “appropriate,” like saying that misogyny exists in her professional field or denouncing a sexual crime committed by a powerful man. It’s always better to stay quiet and just let the abuser have his way. If the woman could also manage to say “thank you” after that, it would be even better. (For the record: Women should also refrain from using irony.)

But I don’t need to go very far to prove that we have good reasons to yell. Just look at a few random acts of gender-based violence in Brazil in the past few months: A male detainee strangled his girlfriend to death inside a prison cell because she restated her desire to end their relationship during the visit. A young man pushed his ex-girlfriend in front of a bus because she told him she was pregnant and he had already planned an exchange trip to Canada. A woman who told the police that her ex-partner was spying on her with a secret camera was stabbed to death by him — in a police vehicle on their way to a police station.

These are extreme manifestations of the unequal power relations between men and women — real-life, concrete expressions of a social dynamic that forces women to stay in a subordinate position, always speaking at a low volume and cowering. The full spectrum of gender-based violence also encompasses but is not limited to sexual harassment, domestic battering, sexual exploitation, violation of reproductive rights, “honor” killings and rape. Not to mention all kinds of threats and abuses of power that hurt women physically, sexually, economically and psychologically.

And what is the only unanimously acceptable response to these acts of violence? Showing deference to the aggressors and keeping one’s mouth shut, of course. It really doesn’t matter that we might carry this burden for the rest of our lives, etched in our consciousness and stored in our tense necks and shoulders. How a woman could possibly heal from a traumatic experience is not the main concern here. Tactfulness, discretion and the responsibility of keeping men safe from unjust accusations are more important.

I spent a few years in a psychologically abusive relationship that left me all hunched over and defensive. After it ended, every time I decided to talk or write about what I’d been through — even in the vaguest terms — I experienced a concerted backlash, an attempt to silence me that pushed me more and more toward the domain of the hysterical, exaggerated, resented woman. In many cases, nothing is easier than condemning a woman to a social and professional limbo. The more powerful the abusers are, the less people believe the victims and the more difficult it is to get material proof.

Every single woman in my self-defense course had some horror story. Learning how to block, evade, immobilize and disarm potential attackers was not the hardest task. The most difficult was the yelling. Our female instructor, Heloíse Fruchi, told us that when we faced our imaginary aggressor, we should look him in the eye and shout as loud as we could. Anything, really, could work: “No!” or “This is Sparta!” or “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!” Some of us simply couldn’t do it, having spent an entire life being courteous and delicate.

During our classes, we have blushed, giggled and apologized to one another a hundred times. I’ve found myself lowering my eyes and doing a common pleading gesture (hands out, palms up) every time I faced the prop that I was supposed to fight back against. We’ve found out that we walk, talk and write in perpetual dread — and that we do not particularly fear the stranger who might drag us into an alley and rape us as much as we fear our own male friends, neighbors, relatives, bosses and partners. Because it seems that — more often than one might think — they love us and respect us only to the extent that we behave in a pleasing way. The minute we step out of line and begin to entertain ideas of our own, we become vulnerable.

In other words, for women it’s always a lose-lose scenario: Be quiet and spend 10 years in therapy; be delicate and suffer from a chronically stiff neck; be firm and get ostracized; be loud and get punished.

Those lessons that begin at age 7 teaching us to be courteous and deferential are partly to blame. If only we were taught instead to yell and scream, while kicking and cursing like a pirate. Maybe that couldn’t prevent abuse. The ultimate responsibility, of course, is not on us; it’s on the abusers. But at least we wouldn’t have to lead those permanently stiffened, suffocated lives.

Vanessa Barbara, a contributing opinion writer, is the editor of the literary website A Hortaliça, and the author of two novels and two nonfiction books in Portuguese.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on November 12, 2017, on Page SR9 of the New York edition with the headline: How I Learned to Yell.